Today, 200 years ago, one of the greatest feminist artists of her time — Rosa Bonheur — was born in Bordeaux. We shined a spotlight on Rosa and her famously eccentric, beautiful château on the edge of the Fontainebleu forest, fittingly dubbed Château de Rosa Bonheur, in our May/June 2021 issue of MFCH Magazine.

Read our feature to learn more about this prolific painter, and the place she called home, below!

SUBSCRIBE TO THE MAGAZINE

She kept lions as pets, smoked cigars, wore men’s clothing, was a regular visitor to slaughterhouses and, when the Prussians invaded France, offered up her services to defend her homeland, only to be laughed out of the room.

Born in 1822, Bonheur was one of the most unconventional yet critically acclaimed and financially successful painters of her time. Admired for her precise and evocative depictions of animals, Bonheur won medal after medal at the Paris Salons as a young woman, earning her the misogynistic but genuinely earnest praise: “She paints like a man.”

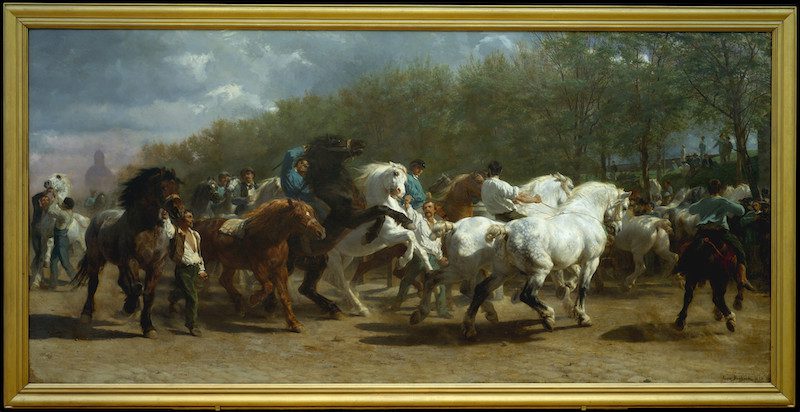

Bonheur sold her artwork primarily to the British and American markets. Marché aux chevaux de Paris (“The Horse Fair”), a monumental canvas that now hangs in New York City’s Metropolitan Museum, fetched a handsome sum of 40,000 French francs (roughly three times more than what her contemporaries could usually hope for).

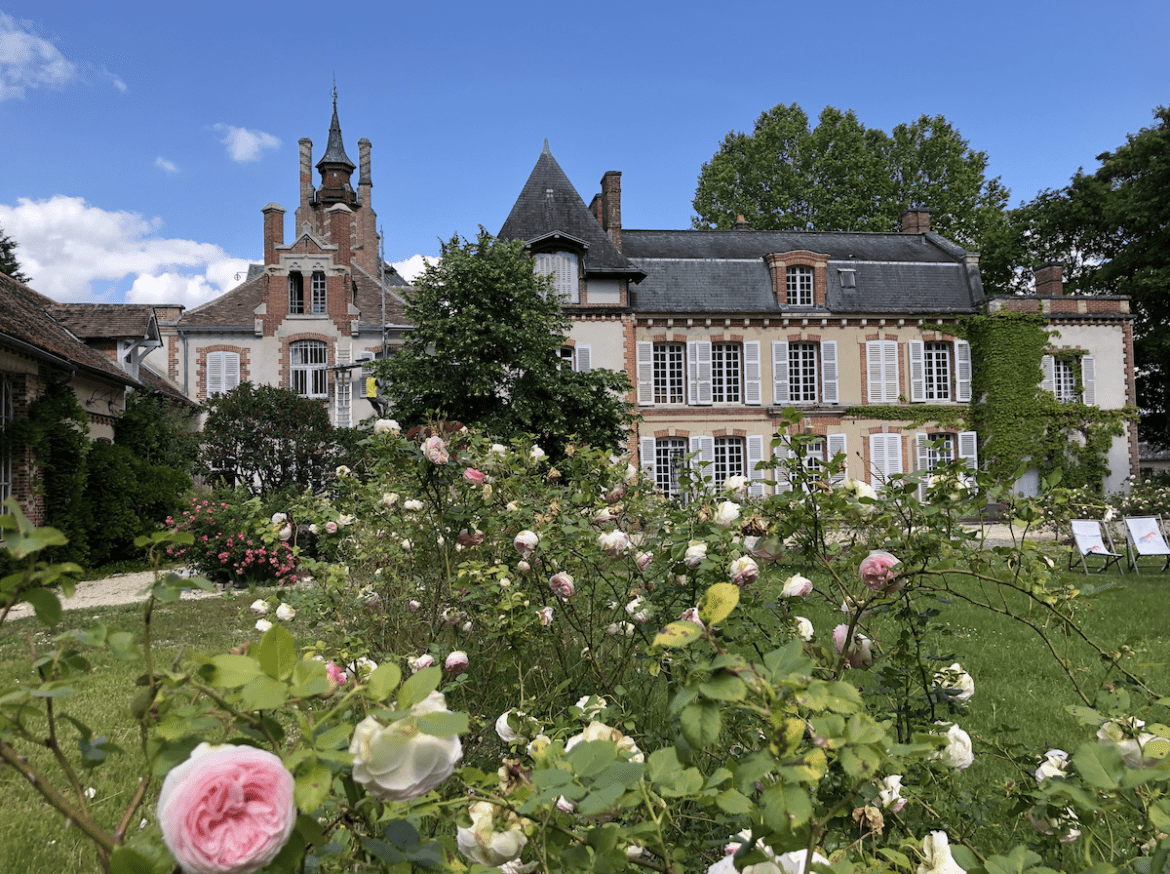

This sum allowed Bonheur to purchase her château in 1859, thus becoming the first woman in France to own property due to the fruits of her own labor. An old manor house from the 15th century, the Château de Rosa Bonheur sits on the edge of the Fontainebleau forest, part of a hamlet nestled in a quiet elbow of the Seine.

At age 37, Bonheur settled in with her menagerie, her life-long partner, Nathalie Micas, and Micas’s open-minded mother. Here, she received illustrious guests, including Empress Eugenie — Napoleon III’s wife — who paid a personal visit to name her Chevalier to the Legion of Honor. “Genius has no sex,” the Empress is believed to have said, as she pinned the award to Bonheur’s blouse.

Young girls in the United States were commonly gifted Rosa Bonheur dolls for Christmas. Queen Victoria requested a private viewing of Marché aux chevaux de Paris before it shipped to America. The famous French composer, Georges Bizet, wrote an ode in her name and John Ruskin, the most eminent art critic of his generation, hastened to meet her while she was in England (if only to disagree about what color she painted her shadows). During her lifetime, Bonheur had, without a doubt, become an establishment.

Yet, fast-forward to today, and most people have never heard of Bonheur. Mention her name in Paris, and you’ll be pointed in the direction of a popular gay club in the Buttes-Chaumont park. Given Bonheur’s status as a 19th-century rockstar, it is hard to compute just how thoroughly the next century forgot her.

It wasn’t until the late 1990s that a retrospective of her work was first held, and many of her paintings remain unhung, unceremoniously stored away in museums’ collections. Supportive of the effort to remember Bonheur, not just as a lesbian and a potential icon but as an artist in her own right, comes from Katherine Brault, a former communications specialist and current owner of the late artist’s Château, which she successfully petitioned to turn into an impressive museum.

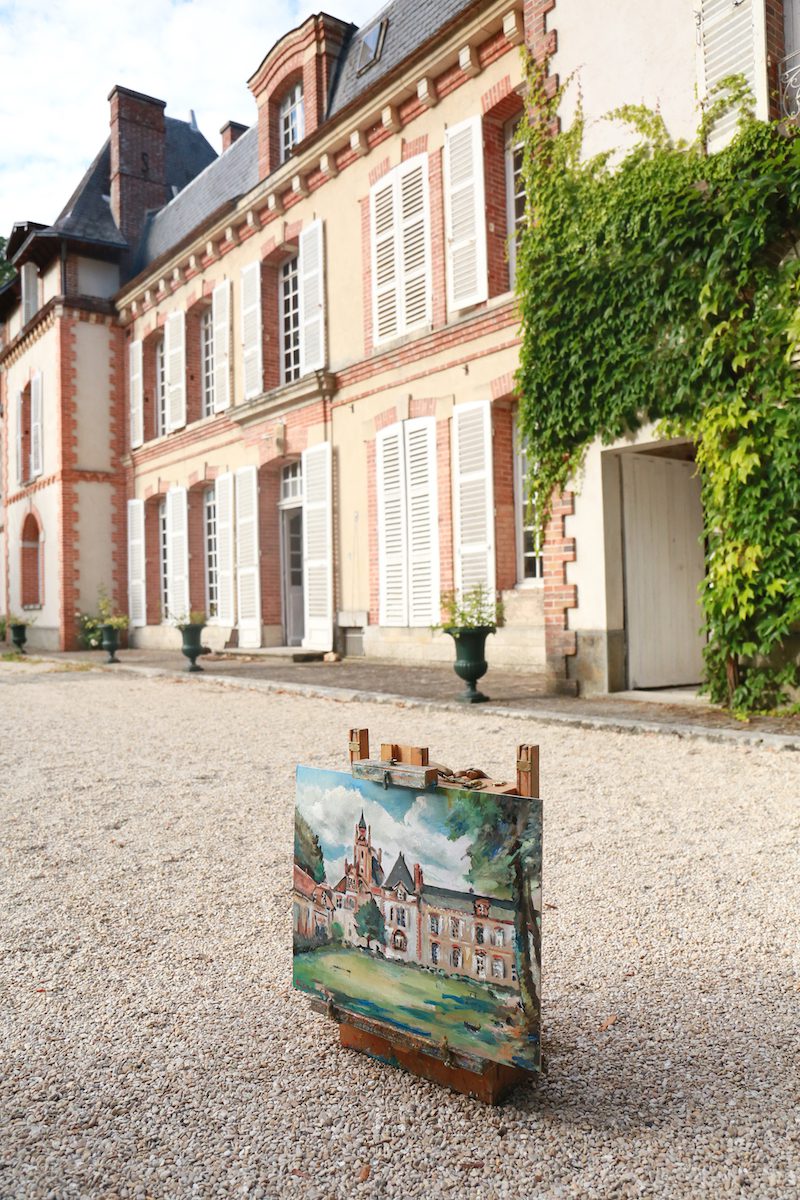

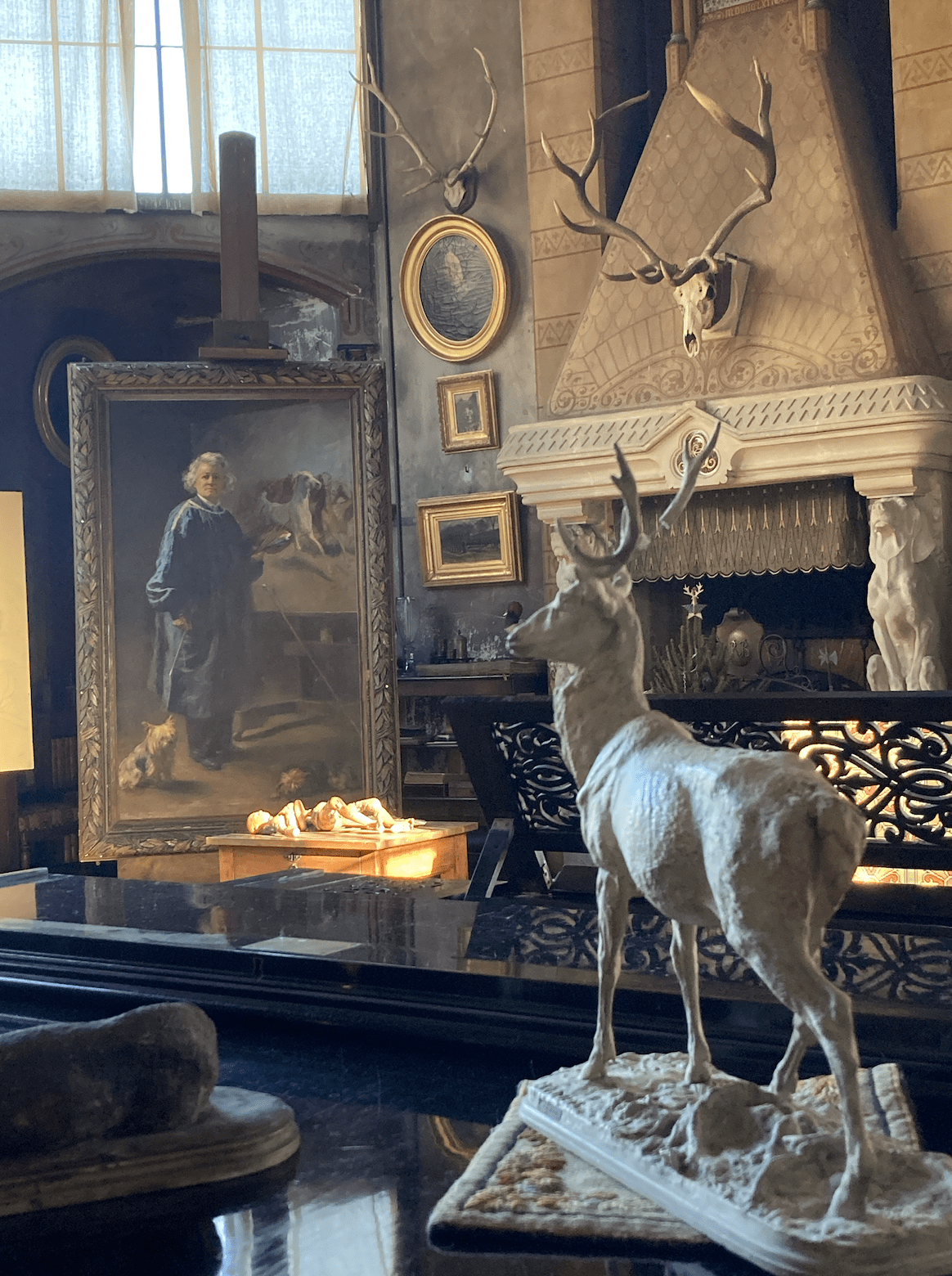

A local from Fontainebleau, Brault remembers coming to By as a child. “I didn’t like it at all,” she recalled. “It was dark and dismal and kitschy. I didn’t know what to make of all these paintings of animals.” But when she returned to scout the property as an adult in the late 2010s, she fell in love. “How could such a place still exist?” she wondered. The estate, passed on by Bonheur to her last domestic partner, Anna Klumpke, had stayed within the family. Hardly anything in the artist’s studio had been moved.

For Brault, convincing bankers to back her project — founding an association for Bonheur lovers — was an uphill battle. During her first-time appointments, she was systematically asked about a husband she did not have.

“Here we are, 120 years later, and these are the same questions Bonheur must have faced. Nothing has changed.”

But Brault prevailed, founding the association, launching a donation campaign, securing a generous grant from the French state and even receiving a visit from President Emmanuel Macron.

The keys to the Château, when Brault finally received them, weighed nearly 11 pounds. Five years later, she and her daughters are still sorting through many of the documents, prints and sketches they found in the attic, hoping to shed more light on the overlooked pioneer’s life as an artist.

“Animal painting may not be as fashionable today as it once was,” said Brault. “But what makes Bonheur truly modern is that she thought animals had a soul. She considered animals equals and believed they truly understood humans. “At a time when people were still debating whether women could even be considered equal to men, that’s revolutionary.”

Her love of animals may have been at the heart of Bonheur’s work, but it occasionally wreaked havoc at home. Bonheur once returned from a trip to the Pyrénées with an otter to keep as a pet, causing much despair when it later escaped its tub to join her stepmother in bed. A pair of wild horses she received from North America were never quite broken in, and one of her lions, Nero, became so unmanageable, that he had to be sent to the Jardin des Plantes (where years later, he was known to still respond to her call). And the tradition appears to continue to this day; on a recent visit to the museum, a household cat managed to slip in and urinate on one of Bonheur’s valuable oil paintings.

Despite the difficult year the museum faced in 2020, there’s reason to be optimistic. Since opening its doors, the Château has enjoyed significant public attention. Visitors can tour the artist’s wing, arranged in much the same way Bonheur left it, right down to her last unfinished canvas, her paintbrush, her palette and a dress draped over a chair. A tea house on the first floor serves homemade pastries and refreshments in Limoges porcelain. Visitors, eager to stay longer, can literally slip into Bonheur’s monogrammed sheets by booking a night in her former bedroom. The museum’s cultural programming includes an outdoor theater, chamber music performances and drawing workshops for children.

Looking forward to 2022, the Musée d’Orsay recently announced an exhibit in Bonheur’s honor to coincide with the bicentennial anniversary of her birth. Part of the focus will be her sketches, which she had refused to sell during her lifetime. These provide a crucial stepping-stone for understanding her path as the astounding, multi-faceted and trail-blazing artist we have learned her to be.

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2021 issue of My French Country Home Magazine

Text by Anna Polonyi – Photos courtesy of Château de Rosa Bonheur